Dispatches from the IGAD Regional Initiative: Setting up a Veterinary Diagnostic Lab in Juba, South Sudan

Kenyan veterinary laboratory technologists, Ms. Teresia Chepkosgei Kenduiywo and Ms. Alice Alego Matole, stand with their South Sudanese “twins” whom they’ve been mentoring for the past year. Everyone works hard, under challenging circumstances to establish an efficient laboratory that can diagnose animal diseases and improve animal health in South Sudan. Photo: Courtesy of Ms. Alice Alego Matole

Teresia Chepkosgei Kenduiywo and Alice Alego Matole, Kenyan veterinary laboratory technologists with two decades of technical experience, arrived at Juba's Central Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory in October 2015, ready to mentor their South Sudanese peers on accurate animal disease diagnosis and effective laboratory management.

Upon their arrival, both women were surprised to learn that the lab lacked something as essential as a microscope.

During the violence of 2013, Ms. Matole explains, most of the lab's equipment was stolen, and what was damaged wasn't repaired. The women found five broken microscopes collecting dust.

"We took spare parts from these broken microscopes to create a functional one," says Ms. Kenduiywo. "It took us a week [to fix it]."

Setting up a fully-equipped veterinary diagnostic lab with trained technicians is central to determining and maintaining the country's livestock's good health, which also benefits its people's well-being, as animal diseases usually impact human health.

The Importance of Cattle in South Sudan

The Food and Agriculture Administration (FAO) reports that South Sudan, a country of around 13 million people, has close to 12 million cattle, over 12 million goats, and 12 million sheep based on data from the country's Ministry of Livestock and Fisheries Industry. These numbers rank South Sudan as the country with the highest livestock per capita in Africa.

At least 80 percent of the country's population relies just on cattle to some extent, FAO estimates.

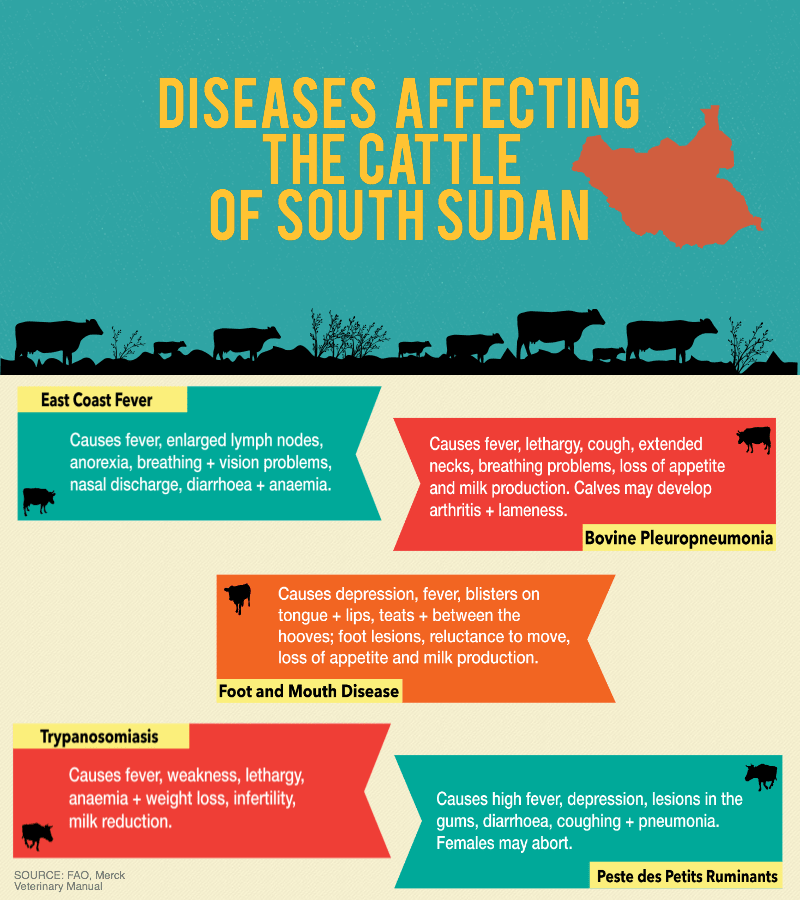

Endemic diseases like peste des petits ruminants or east coast fever, undermine livestock production, threatening the livelihoods of South Sudan’s population. Local and national capacity to control diagnose and control these diseases is severely limited. Photo: FAO/A. Konevski

But in South Sudan, cattle represent much more than food.

Many communities use it to pay a bride's dowry, resolve disputes, or as compensation in murder or adultery cases. Having the largest number of cattle in the area determines personal prestige and earns respect.

"Livestock as an industry is unexplored," Ms. Kenduiywo explains. "It's seen as a pride symbol rather than a commodity that could improve [South Sudan's] food security and economy."

On the other hand, a FAO report explains that conflict has caused "large-scale and long-distance displacement of livestock" as thousands of pastoralists abandon their traditional migration patterns in a desperate search for security. This has increased risks of disease outbreaks such as Foot and Mouth Disease, East Coast Fever, and Trypanosomiasis.

"Not much is known about disease control," adds Ms. Matole. "That's why South Sudan needs a lab to determine the status and quality of health of its animals."

Graphic: Created by Elena Sosa Lerín

Training South Sudan's future veterinary lab technicians

Since late 2015, Ms. Kenduiywo and Ms. Matole have intensely worked with their four South Sudanese young male counterparts, known as "twins," on essential biosafety and hygienic guidelines and protocols, which were practically non-existent before the pair's arrival.

The laboratory has operated without electricity since July 2015 due to the smouldering of the central cable that powered the lab. To preserve animal samples, they're taken to a nearby veterinary research lab supported by FAO, which has freezers run by a generator.

Although Mrs. Kenduiywo and Ms. Matole managed to fix one microscope, there's lab equipment that needs to be repaired and maintained by biomedical engineers — the type of technical capacity missing in the country's animal health sector.

The lab doesn't have a safe waste disposal system. Since there aren't incinerators, the lab's trash is burned in a nearby field, which, as Ms. Kenduiywo explains, is a potential health hazard for the people living nearby. It's suspected that this waste burning is what damaged the lab's main power cable.

But despite these challenges, there have been significant achievements.

The "twins" can now carry out the ELISA test, a quick way to detect and measure antibodies in the bloodstream. They can perform microscopic examinations of blood, saliva, and urine to test for potential infections. They've also learned to use rapid test kits and assist with veterinary surveillance — the ongoing collection, analysis, and monitoring of animal health information.

"Their progress has been impressive," says Ms. Matole. "The most exciting part of my day is to see my twins do something on their own. I know it's not easy for them because they don't have a strong scientific background. They don't get paid, and yet, they still show up to work. That's to be admired, and that's why we enjoy working with them."

Ms. Matole and Ms. Kenduiywo's work in Juba's Central Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory is possible thanks to the support of the governments of Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda through a capacity development initiative by the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), an eight-country regional development block in eastern Africa, as well as the government of South Sudan.

The initiative's objective is to strengthen South Sudanese civil service capacity at both national and sub-national levels. This is accomplished by lending out seasoned civil servants from these three IGAD countries — known as Civil Service Support Officers (CSSOs) — and pairing them up with South Sudanese counterparts, usually referred to as "twins."

Their relationship is one of mentoring, coaching, and close collaboration.

Since 2011, over three hundred CSSOs, working on two-year contracts, have come to South Sudan to support capacity-building efforts in sectors like agriculture, aviation, finance, and public health. Their own countries cover their salaries while other expenses are paid for by the government of Norway, the project's sole donor. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) is responsible for the coordination and implementation of this initiative.

► A version of this story was originally published on September 2016 in the website of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in South Sudan.

Follow me on Twitter: @e_sarin. Email me your thoughts, suggestions, or critiques at: elenasosalerin@gmail.com.